In a poignant reflection on loss and accountability, Edith Nyachuru articulates a heart-wrenching claim: "I blame the Church for my brother’s death." Her brother, Guide Nyachuru, tragically drowned during a holiday camp run by John Smyth, a former barrister who had previously faced serious allegations of child abuse in the UK. This tragedy, which unfolded almost 31 years ago at a camp in Marondera, Zimbabwe, has thrust the Church of England's history of inaction into the spotlight, raising pressing questions about their responsibility to protect vulnerable children.

Smyth, who relocated from Britain to Zimbabwe in 1984, had already been implicated in severe abuses against boys as part of an Anglican-linked charity. The findings of a 1982 report prepared by clergyman Mark Ruston documented horrific acts of corporal punishment and sexual misconduct, but tragically, these revelations failed to prevent Smyth from establishing Zambesi Ministries, where he continued similar abusive practices in Zimbabwe.

Guide’s brother, who was looked forward to becoming head boy at his school, attended the camp as a festive gift from a sibling. Just hours after arriving, the family received devasting news of his death, allegedly due to drowning after swimming naked—an unsettling tradition at the camp overseen by Smyth. Eyewitness accounts have since described an alarming pattern of conduct, noting Smyth's fixation with nudity and his troubling behavior, which left many boys feeling confused yet intimidated.

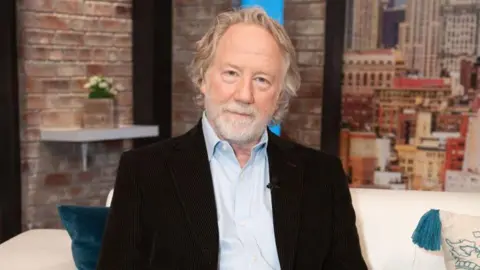

Coltart, a legal professional, uncovered significant abuse patterns exposed in the wake of Guide's death, demonstrating how Smyth wielded authority over the boys and exploited his status. Far from being reprimanded, Smyth maintained his influence, disregarding legal attempts to halt his activities. Despite international outcry and reports of dire abuse, Smyth manipulated his connections to avoid legal consequences.

The Church's failure to intervene has drawn significant ire, particularly in light of a recent apology from Archbishop Justin Welby acknowledging the church's shortcomings. Nyachuru described the apology as insufficient, intensifying her campaign for accountability within the institution that allowed Smyth's predatory behavior to persist unchecked.

Both Coltart and Nyachuru urge the Church of England and related institutions to reflect on their failures and take responsibility for those who suffered, advocating for outreach to victims grappling with the long-term impacts of Smyth's abuse—many of whom remain silent due to trauma.

As Zimbabweans reflect on the legacy of this tragedy, the Nyachuru family’s story serves as a powerful reminder of the community's desperate need for transparency, justice, and healing from both loss and trauma.

Smyth, who relocated from Britain to Zimbabwe in 1984, had already been implicated in severe abuses against boys as part of an Anglican-linked charity. The findings of a 1982 report prepared by clergyman Mark Ruston documented horrific acts of corporal punishment and sexual misconduct, but tragically, these revelations failed to prevent Smyth from establishing Zambesi Ministries, where he continued similar abusive practices in Zimbabwe.

Guide’s brother, who was looked forward to becoming head boy at his school, attended the camp as a festive gift from a sibling. Just hours after arriving, the family received devasting news of his death, allegedly due to drowning after swimming naked—an unsettling tradition at the camp overseen by Smyth. Eyewitness accounts have since described an alarming pattern of conduct, noting Smyth's fixation with nudity and his troubling behavior, which left many boys feeling confused yet intimidated.

Coltart, a legal professional, uncovered significant abuse patterns exposed in the wake of Guide's death, demonstrating how Smyth wielded authority over the boys and exploited his status. Far from being reprimanded, Smyth maintained his influence, disregarding legal attempts to halt his activities. Despite international outcry and reports of dire abuse, Smyth manipulated his connections to avoid legal consequences.

The Church's failure to intervene has drawn significant ire, particularly in light of a recent apology from Archbishop Justin Welby acknowledging the church's shortcomings. Nyachuru described the apology as insufficient, intensifying her campaign for accountability within the institution that allowed Smyth's predatory behavior to persist unchecked.

Both Coltart and Nyachuru urge the Church of England and related institutions to reflect on their failures and take responsibility for those who suffered, advocating for outreach to victims grappling with the long-term impacts of Smyth's abuse—many of whom remain silent due to trauma.

As Zimbabweans reflect on the legacy of this tragedy, the Nyachuru family’s story serves as a powerful reminder of the community's desperate need for transparency, justice, and healing from both loss and trauma.