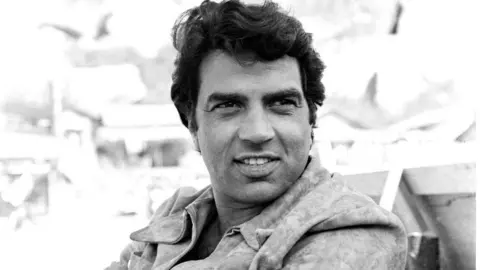

Shapurji Saklatvala's name might not be prominent in mainstream historical narratives, but his life story, as a descendant of the Tata family, is anything but ordinary. A cotton merchant's son, Saklatvala chose a path of political activism and radicalism in stark contrast to his rich relatives, who were at the helm of one of the world's most substantial business empires, the Tata Group.

Born into privilege, his upbringing diverged notably from that of his affluent cousins, as he was determined to address what he saw as systemic injustices within society. Unlike his relatives, who went on to maximize their business interests, Saklatvala's journey led him to become a prominent figure in the British political sphere, advocating fiercely for India's struggle against colonial rule.

This ambitious venture into politics was influenced by various personal and societal factors. His early life was marked by family tensions, particularly with his cousin Dorab, who resented the attention Saklatvala received from their influential grandfather. This familial discord provoked a desire for independence and a quest for a different life, steering Saklatvala away from the family business.

The devastating bubonic plague that swept through Bombay in the late 1890s deeply affected Saklatvala. He witnessed how this epidemic ravaged the city's lower classes while leaving the wealthy largely untouched. In this chaos, he found purpose, working alongside scientists like Waldemar Haffkine to advocate for vaccination and public health awareness.

Saklatvala's marriage to Sally Marsh, a woman from a working-class background, further broadened his perspective on the living conditions of the lower socioeconomic strata in Britain. This relationship compelled him to immerse himself in social issues and ignited his passion for the rights of the marginalized.

Transitioning to life in the UK in 1905, he quickly gravitated towards political activism. By joining the Labour Party in 1909 and later the Communist Party, he fully embraced the ideologies of social change and class struggle. His impactful speeches brought him to the forefront of political discourse, culminating in his election to the British Parliament in 1922, where he ardently supported Indian independence.

His parliamentary career was fraught with confrontations, particularly with the likes of Mahatma Gandhi, whose non-violent protest strategy conflicted with Saklatvala’s more radical approaches. Despite their disagreements, both men shared an overarching goal: the abolition of British colonial rule in India.

Saklatvala's fierce advocacy did not come without consequence. He faced the ire of British officials who branded him a "dangerous radical communist," leading to travel bans and eventually the loss of his parliamentary seat in 1929. Nevertheless, his resolve to fight for India's freedom did not wane, and his legacy continued long after he passed away in 1936.

Ultimately, Saklatvala remained a pivotal figure in both British politics and the Indian independence movement, with his ashes buried in London alongside those of his parents and Jamsetji Tata, symbolizing his reconnecting with his family's roots and their legacy in history. His story serves as a testament to the intricate tapestry of personal choice, societal response, and political activism during a time of great upheaval.