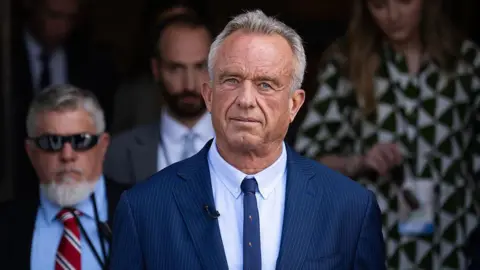

In fiery Senate testimony this week, U.S. Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. once again set his sights on the nation's top public health agency, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

His appearance came days after he suddenly fired the new CDC director, Susan Monarez, provoking a group of senior staff to resign in protest.

At the hearing, when asked for an explanation, Kennedy claimed he had asked Ms. Monarez if she was a 'trustworthy person' and she had replied 'no', to some disbelief from his opponents in the room.

He then admitted he had once described the CDC as the 'most corrupt' agency in government, and strongly hinted he's not finished with his plans to shake up the organization.

Kennedy's words have sparked a furious backlash, with many doctors and scientists increasingly concerned that America's public health systems are being dangerously compromised.

It's a conflict that could have a significant impact not just on health policy in the U.S. but across the world. In the past, the CDC has been instrumental in global health, leading the response to crises from famine, to HIV, to Ebola.

Founded in 1946, the CDC tracks emerging infectious diseases and is also tasked with tackling long-term or chronic conditions such as heart disease and cancer. It operates more than 200 specialized laboratories and employs 13,000 people, although that number has been cut by around 2,000 since President Trump returned to office.

It does not approve or license vaccines; that responsibility lies with the Food and Drug Administration. But it does produce official recommendations on who should receive which vaccines through a panel of experts - known as the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) - and monitors their side effects and other safety concerns.

Vaccine Dispute

It was Kennedy's record on vaccines that particularly worried many public health experts when he took office in February. An activist group he ran for eight years, Children's Health Defense, repeatedly questioned the safety and efficacy of vaccination.

He has described the Covid jab as the 'most deadly in history' and has blamed rising rates of autism on vaccines, an idea that has been categorically debunked by large scientific studies over many years.

So feathers were seriously ruffled just weeks into his tenure when it emerged he had hired a noted vaccine critic, David Geier, to look again at the CDC data on that scientifically disproven link.

Then in June, Kennedy suddenly sacked the entire ACIP panel which advises the CDC on vaccine eligibility after accusing all 17 members of being 'plagued with persistent conflicts of interest'.

A new committee, handpicked by the administration, now has the power to change, or even drop, critical recommendations to immunize Americans for certain diseases, as well as shape the childhood vaccination program, although the CDC itself still has the final say on whether to accept that advice.

In his testimony, Kennedy stood his ground, accusing Monarez of lying about their exchange and describing her dismissal as 'absolutely necessary'.

Ms. Monarez's sacking led to a fresh wave of resignations at the agency as senior staff continue to walk out. Over the last two weeks, the CDC has lost its chief medical officer, its director of immunization, and its director of emerging diseases, among others.

Global Repercussions

The next flashpoint could come later this month. On September 18, the CDC's new vaccine advisory panel is due to meet to discuss Covid vaccines and other shots, including for hepatitis B and the RSV virus.

The panel's recommendations and the CDC's response will be carefully scrutinized, not just in the U.S. but around the world. 'What happens in America is of great importance,' says Anthony Costello, a former director at the World Health Organization and a professor of public health at University College London.

In the past, CDC teams have also had a major hands-on role in global health protection. For instance, in 2015, the agency had 3,000 staff working on the Ebola outbreak in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia, with 1,200 of those on the ground in West Africa.

Given these developments, there are rising concerns about the potential for the politicization of public health. Former CDC officials warn that a weakened CDC may leave the U.S. less prepared for any future health emergencies, a situation that could have dire implications not just domestically, but globally.