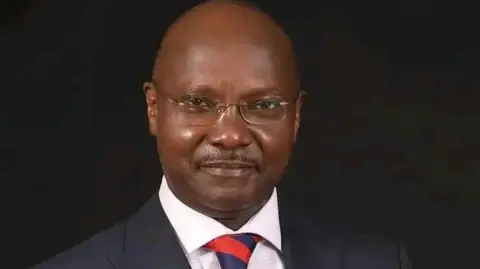

In a shocking incident that has gripped both Cambodia and Thailand, Lim Kimya, a 73-year-old former opposition parliamentarian, was shot dead in Bangkok’s royal quarter. The assassination, executed with chilling precision, has raised troubling questions about potential foreign involvement and the ongoing dangers faced by political dissidents in Southeast Asia.

Security camera footage captures the frightening event: a figure calmly parking a motorbike, removing his helmet to reveal his face, and moments later a flurry of gunfire is heard, leaving Lim Kimya fatally wounded. By the time emergency responders arrived, it was too late—he was pronounced dead on the scene. The police later determined that Lim had been struck by two bullets to the chest.

Lim Kimya, a prominent member of Cambodia's now-banned opposition party, the CNRP (Cambodia National Rescue Party), had arrived in Thailand hours earlier with his wife after a bus journey from Cambodia. In a poignant reaction, the daughter of CNRP leader Kem Sokha stated, “No one but the Cambodian state would have wanted to kill him.”

Known for his resilience and dedication to his political beliefs, Lim Kimya remained in Cambodia even when his party faced government suppression. The CNRP, which posed a serious challenge to Prime Minister Hun Sen’s long-standing grip on power, was dissolved in 2017 amid accusations of treason. In a move that struck fear into the hearts of many within the opposition, Kem Sokha received a lengthy 27-year prison sentence earlier this year.

While high-level political assassinations are relatively rare in Cambodia, the killing of activists is not unprecedented. Past tragic instances, like the murders of critic Kem Ley in 2016 and environmentalist Chut Wutty in 2012, underline a pattern of violence against those who challenge the ruling regime.

As Thai police identified Lim Kimya's alleged assassin—an ex-military officer now working as a motorbike taxi driver—concerns linger regarding the integrity of the investigation. A history of political deal-making and cross-border repression complicates aspirations for justice. Phil Robertson, an expert in human rights in Asia, has pointed to a troubling trend wherein dissidents are allegedly exchanged between countries for political and economic advantages—a dangerous dance that heightens the risks for activists seeking refuge.

In recent years, Thailand has faced scrutiny for forcibly returning Cambodian dissidents, including those recognized as refugees by the United Nations, back to Cambodia, where they could face potential imprisonment. The atmosphere of fear is palpable as Thailand has been accused of complicity in such actions, further stifling dissent across the region.

The burgeoning administration of Prime Minister Hun Manet, who succeeded his father Hun Sen, has yet to signal profound changes in its approach toward opposition figures. The continuance of political repression further exacerbates concerns that Cambodia remains on a path of authoritarian governance, despite some speculation about a softer rule.

As the international community watches closely, Thailand may find itself under increasing pressure to address this high-profile assassination transparently. The stakes involve not only justice for Lim Kimya but the broader issues of human rights and political safety in a region marked by rising authoritarianism and cross-border aggression against dissenters.

Security camera footage captures the frightening event: a figure calmly parking a motorbike, removing his helmet to reveal his face, and moments later a flurry of gunfire is heard, leaving Lim Kimya fatally wounded. By the time emergency responders arrived, it was too late—he was pronounced dead on the scene. The police later determined that Lim had been struck by two bullets to the chest.

Lim Kimya, a prominent member of Cambodia's now-banned opposition party, the CNRP (Cambodia National Rescue Party), had arrived in Thailand hours earlier with his wife after a bus journey from Cambodia. In a poignant reaction, the daughter of CNRP leader Kem Sokha stated, “No one but the Cambodian state would have wanted to kill him.”

Known for his resilience and dedication to his political beliefs, Lim Kimya remained in Cambodia even when his party faced government suppression. The CNRP, which posed a serious challenge to Prime Minister Hun Sen’s long-standing grip on power, was dissolved in 2017 amid accusations of treason. In a move that struck fear into the hearts of many within the opposition, Kem Sokha received a lengthy 27-year prison sentence earlier this year.

While high-level political assassinations are relatively rare in Cambodia, the killing of activists is not unprecedented. Past tragic instances, like the murders of critic Kem Ley in 2016 and environmentalist Chut Wutty in 2012, underline a pattern of violence against those who challenge the ruling regime.

As Thai police identified Lim Kimya's alleged assassin—an ex-military officer now working as a motorbike taxi driver—concerns linger regarding the integrity of the investigation. A history of political deal-making and cross-border repression complicates aspirations for justice. Phil Robertson, an expert in human rights in Asia, has pointed to a troubling trend wherein dissidents are allegedly exchanged between countries for political and economic advantages—a dangerous dance that heightens the risks for activists seeking refuge.

In recent years, Thailand has faced scrutiny for forcibly returning Cambodian dissidents, including those recognized as refugees by the United Nations, back to Cambodia, where they could face potential imprisonment. The atmosphere of fear is palpable as Thailand has been accused of complicity in such actions, further stifling dissent across the region.

The burgeoning administration of Prime Minister Hun Manet, who succeeded his father Hun Sen, has yet to signal profound changes in its approach toward opposition figures. The continuance of political repression further exacerbates concerns that Cambodia remains on a path of authoritarian governance, despite some speculation about a softer rule.

As the international community watches closely, Thailand may find itself under increasing pressure to address this high-profile assassination transparently. The stakes involve not only justice for Lim Kimya but the broader issues of human rights and political safety in a region marked by rising authoritarianism and cross-border aggression against dissenters.