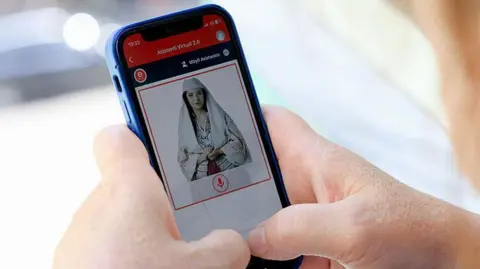

Han Tae-soon’s long journey to find her daughter, Kyung-ha, who was taken from her in 1975, has culminated in a lawsuit against the South Korean government. Despite decades of searching, Han didn’t see Kyung-ha again until 2019, when they discovered each other through a DNA matching service and learned that Kyung-ha had been raised in America under the name Laurie Bender.

Implicating the South Korean government, Han alleges that Kyung-ha was abducted as a child and that her adoption to an American family was facilitated without proper oversight or consent from Han. She has joined scores of others who have spoken out about a history of illegal adoptions, human trafficking, and fraud in South Korea's overseas adoption program, which has seen an estimated 170,000 to 200,000 children sent abroad since its inception in the 1950s.

A seminal investigation conducted in March revealed a series of human rights abuses by successive governments, prompting fears of wider legal repercussions for government bodies. Han is set to present her case in court next month amid increasing scrutiny of the system, which has faced criticism for being profit-driven and poorly regulated.

Government officials expressed sympathy for people affected by the illegal practices, with promises to reassess their approach based on upcoming rulings. Han's case marks a significant moment in which the first biological parent of an overseas adoptee seeks damages from the government, setting a precedent that may inspire more individuals to pursue legal action.

Han has expressed her desire for accountability, stating that despite her exhaustive efforts to locate her daughter over the years, she has never received an apology from authorities. Meanwhile, Kyung-ha recounted a harrowing story of being approached by a stranger as a child, which resulted in her abandonment and eventual adoption in the United States under false pretenses.

The adoption program grew from Korea’s post-war realities, but as the demand for adoptive children in the West surged, it led to questionable practices, including the alleged kidnapping of children and falsification of records. Experts suggest that both private adoption agencies and the government share responsibility, arguing that systemic failures allowed these illicit activities to be perpetuated.

Recent policy changes aim to reduce overseas adoptions and improve the adoption landscape, emphasizing the need to treat this past with sensitivity. However, adoptees like Han and their birth parents continue to grapple with the emotional scars left behind. As connections strained by language barriers and distance complicate reunion efforts, Han remains committed to bringing attention to these enduring issues, asserting that no amount of restitution can restore what she has lost.