WASHINGTON (AP) — After serving with the U.S. Marine Corps in Iraq, Julio Torres proudly bears tattoos of the American flag and Marine Corps insignia on his arms. However, after facing challenges including post-traumatic stress disorder and drug addiction, he finds purpose as a pastor, delivering messages of hope and freedom to those combating similar issues.

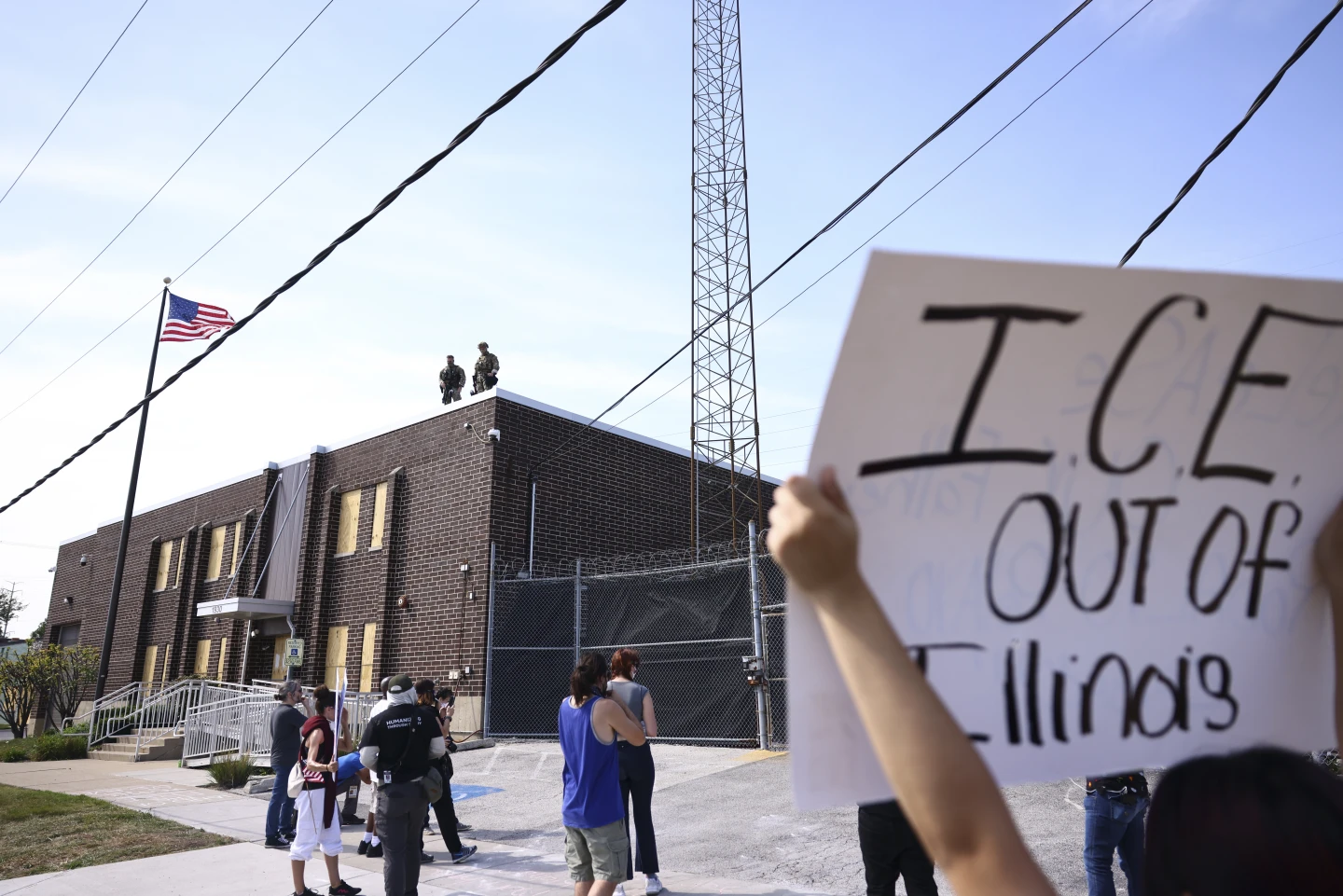

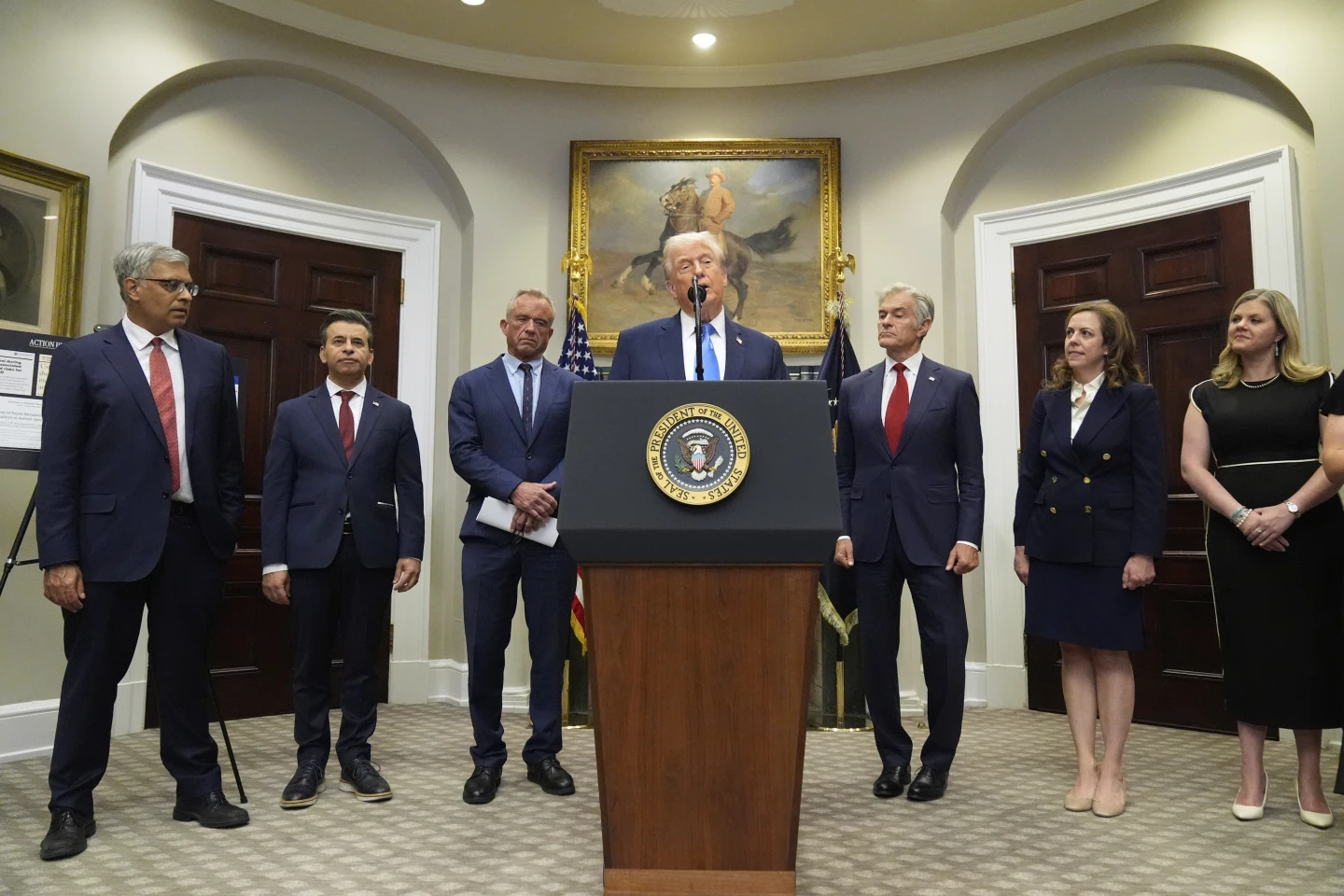

Today, Torres's community in East Texas, which he fought to protect, feels more like a prison than the land of the free. Under President Donald Trump's rigorous immigration agenda, Torres, who migrated to the U.S. legally at age five, experiences fear as he navigates a landscape marked by mass deportations. Despite having a green card and military service records, he was detained by immigration authorities last year under the Biden administration. With Trump amplifying U.S. Customs and Immigration Enforcement raids, Torres’s anxiety about deportation intensifies.

Torres articulates his emotional turmoil: “It breaks my heart that I fought for this nation to raise my children in this nation, and now I have to pull my children out of this nation if I get deported. Then what did I fight for?”

He is part of a larger group—more than 100,000 military veterans in the United States do not have citizenship. Despite military recruitment often presenting service as a pathway to citizenship, many veterans face renewed risks of deportation due to stringent immigration policies.

In response, Democrats in Congress are raising alarms over the recent detentions of military veterans by ICE. A bipartisan bill introduced aims to protect these veterans by allowing them a chance to apply for lawful immigration status. Rep. Mark Takano, a Democrat from California, highlights the essential role of non-citizen military personnel in national security.

Torres recalls the anger he felt being sent to an immigration detention center after arriving back from visiting relatives in Mexico, where he was apprehended despite holding a green card. The criminal charges from years ago now threaten his status and future in a country he devoted himself to protect.

“I was angry that I served a nation that now did not want me,” he recalls, expressing how the environment of fear restricts his ability to provide for his family. As laws change, many veterans find themselves at risk, struggling more intensely with mental health issues.

Other deported veterans also tell traumatic stories of fear and isolation in the countries they returned to after service. David Bariu, deported to Kenya after serving in the U.S. military, explains how living in a volatile area forced him to hide his service record.

As citizens reflect on immigration and military service, activities in Congress continue to evolve, with efforts to change the narrative around military veterans, acknowledging their contributions regardless of citizenship status. Torres remains hopeful that the political divide can be bridged—recognizing immigration as a veterans’ issue.

“This is about a veteran,” he concludes with a poignant reminder of his belonging to the nation he served. “I love my nation. Even if this nation does not currently consider me part of it, I still consider it my homeland.”