The recent passage of a controversial development law in Brazil has raised serious concerns regarding the potential for environmental degradation and human rights infringements, particularly in the Amazon rainforest. According to Astrid Puentes Riaño, a UN special rapporteur, this new legislation represents a "rollback for decades" of protections in Brazil, placing the country's rich biodiversity at significant risk.

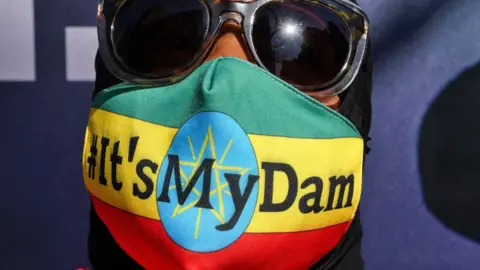

The law, designed to streamline the approval process for large infrastructure projects including roads, dams, and energy ventures, has been criticized for its potential to exacerbate deforestation. Astrid Puentes Riaño highlighted the risk of "significant environmental harm and human rights violations," stressing that the move could jeopardize long-standing efforts to safeguard the Amazon.

Legislators have approved a plan that simplifies the environmental licensing process, although it awaits the president’s formal endorsement. Critics have dubbed it the "devastation bill," predicting it would foster environmental abuses and lead to increased deforestation. Supporters argue that the new licensing regime would minimize bureaucracy, allowing companies to navigate development approvals more efficiently.

Key elements of the law permit developers to self-declare their environmental impact for smaller projects through an online form—a procedure that proponents argue enhances efficiency, yet opponents warn lacks necessary oversight. Riaño cautioned that lighter regulations could apply to mining projects in vulnerable areas and may facilitate Amazon deforestation by bypassing thorough assessments.

Environmental assessments would see reduced requirements for consultation with indigenous populations unless they are directly impacted, which has drawn further criticism from UN experts. This aspect of the law raises concerns over diminished participation from local communities in decision-making processes that affect their land and livelihoods.

As Brazil's Climate Change Minister, Marina Silva, labels the bill as a "death blow" to environmental protections, calls for a veto from President Lula da Silva grow louder. He has until August 8 to decide whether to approve the legislation. If vetoed, it is expected that a conservative-leaning congress may contest that decision.

Critics assert that the bill contradicts constitutional rights to an ecologically balanced environment, which could lead to legal challenges if enacted. The consequences of the law are alarming, as studies suggest it could lift protections on over 18 million hectares of land—roughly the size of Uruguay—indicating far-reaching implications for both the ecosystem and the indigenous populations reliant on its health.

Experts within Brazil's Climate Observatory regard the legislation as the "biggest environmental setback" the nation has seen since the period of military dictatorship, a time marked by substantial deforestation and the displacement of indigenous peoples. With a history of environmental degradation linked to agriculture and mining, these developments could have dire consequences for the Amazon and its stewards.