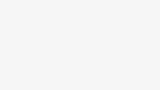

Driving through Mezzeh 86, a working-class neighborhood in Damascus, one encounters a new power dynamic following the significant changes in Syria's political landscape. Controlled by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), a Sunni Islamist group originating from al-Qaeda, the area comprises many members of Bashar al-Assad's Alawite sect, which holds a prominent yet contentious position in the nation's history.

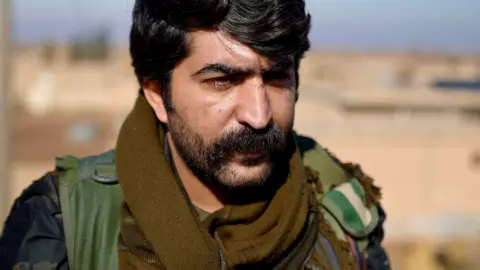

For over half a century, the Alawites dominated the political scene during the Assad family's rule, positioning themselves within the government and military. However, with the regime's recent collapse and the emergence of HTS, there is considerable fear within the community regarding potential reprisals from those who oppose the Assads as they grapple with a chaotic environment left behind after 24 years of Bashar al-Assad's reign.

Despite a palpable sense of anxiety, locals like Mohammad Shaheen, a pharmacy student, emphasize the socioeconomic disparities within the Alawite community, arguing that wealth and power were heavily concentrated among the Assad family, leaving many poor and disenfranchised. Acknowledging mixed feelings about their previous alignment with the regime, residents now express a desire to move forward while distancing themselves from past associations.

Further complicating the situation, there are claims of reprisal killings across the country, though substantive evidence linking these acts directly to HTS remains scarce. Community members express cautious optimism, noting that while they have engaged with HTS, intrusions from groups posing as HTS threaten their safety.

Simultaneously, the Christian minority, represented by figures like Youssef Sabbagh, remain hopeful for a future free from dictatorship yet express trepidation over HTS's Islamist affiliations. They share a mutual desire among various religious communities to prevent Syria from devolving into environments similar to Afghanistan or Libya, emphasizing the need to secure the rights and place of minorities within a diverse society.

Traveling further southeast to Suweida, home to a majority Druze population, the atmosphere is notable for its mixture of celebration and apprehension. Druze activists, such as Wajiha al-Hajjar, have made significant strides in voicing their rights and preparing for potential challenges from new governance structures, as their community has experienced unique pressures under the Assad regime.

In Suweida's central square, daily gatherings blend celebration of the regime's demise with a determination to ensure continued rights and autonomy for minorities. Such expressions underline the complexity and diversity of Syrian society, suggesting that the path ahead will require an understanding of various cultural identities to foster a genuinely democratic and stable Syria.

As these communities navigate their new reality, the moves made by HTS and other political forces will ultimately determine the future landscape of religious and ethnic coexistence in Syria.