A colossal meteorite, designated S2, has cast light on the resilience of early life following catastrophic events on Earth. Discovered in 2014 and estimated to be between 40 to 60 kilometers in diameter, the S2 meteorite is believed to have struck Earth approximately three billion years ago when our planet was still in its formative years. The impact, which resulted in a crater approximately 500 kilometers wide, generated unprecedented tsunamis and boiled the oceans.

Lead researcher Professor Nadja Drabon from Harvard University emphasizes the profound implications of the impact, stating, "We know that after Earth first formed there was still a lot of debris flying around space that would be smashing into Earth." These findings challenge traditional views of planetary formation and extinction, revealing that while asteroid impacts are typically associated with devastation, they also played a crucial role in fostering early life.

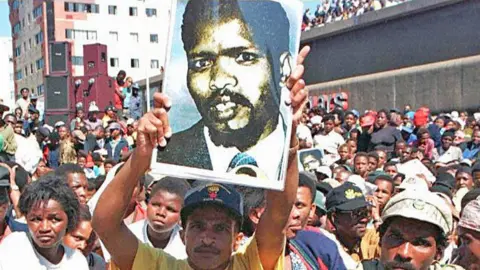

The research team ventured to the Eastern Barberton Greenstone Belt in South Africa to collect rock samples, highlighting the importance of this ancient site. The location preserves remnants of S2’s impact, making it a critical point for understanding early geological and biological processes. Accompanied by local rangers for safety against potential wildlife threats, the team collected spherule particles—tiny rock fragments formed by meteoritic impacts.

Using hammers, the scientists extracted hundreds of kilograms of material to analyze the physical consequences of the S2 collision. The meteorite's formidable force ejected rocks into the atmosphere, creating clouds of molten debris, which then fell back to Earth, mimicking the formation of rain but consisting of fiery rock droplets.

This cataclysm reportedly triggered a tsunami that dwarfs known historical events, such as the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, and generated enough heat to raise ocean temperatures and evaporate significant portions of water. Shockingly, the chaos also churned up vital nutrients, such as phosphorus and iron, into shallow waters, enriching the environment for early microbes.

The research contrasts the long-standing perception of devastating impacts: "Life was not only resilient but actually bounced back really quickly and thrived," Professor Drabon elaborated, likening the process to how bacteria can swiftly repopulate after a cleaning. The evidence suggests that cataclysmic events likely acted as fertilizers, distributing essential ingredients for life globally.

These revelations, recently detailed in the journal PNAS, contribute to a broader understanding that ancient impacts may have inadvertently created favorable conditions conducive to the development and proliferation of early life on Earth, offering a new perspective on how biological resilience flourished amidst primordial chaos.