Bala Muhammad, known affectionately as Baba Bala, runs a watch-repair shop nestled in a busy street in Kaduna, Nigeria. His shop is filled with the ticking sounds of various timepieces, reminiscent of a bygone era where watches were essential. With over 50 years in the trade, Baba Bala used to receive up to 100 repair jobs a day; however, the advent of mobile phones has led to a sharp decline in demand for traditional wristwatches.

At 68 years old, he expresses his concerns about the future of his craft, voicing feelings of sadness as customers dwindle. "Some days there are zero customers," he laments, attributing this downturn to the convenience of smartphones, which have largely replaced the need for wristwatches. Once a thriving business that allowed him to provide for his family, build a home, and send his children to school, Baba Bala now faces the reality that his skills may fade into obscurity.

His father, Abdullahi Bala Isah, was a renowned horologist who traveled throughout West Africa providing watch repair services. Baba Bala learned the trade from him at a young age and recalls how it enabled him to earn money while his peers struggled financially in school. He fondly remembers impressing teachers by fixing their timepieces when other repairmen could not.

In recent years, however, the watch-making community in Kaduna has seen a decline. Baba Bala notes that most of his colleagues have either passed away or stopped working, with some choosing to shift to farming instead. Isa Sani, another former watch repairer, voiced his frustration, stating, "Going to my repair shop daily meant sitting down and getting no work." Such sentiments resonate with younger generations, like Faisal Abdulkarim and Yusuf Yusha'u, who have never owned watches and prefer using their phones for timekeeping.

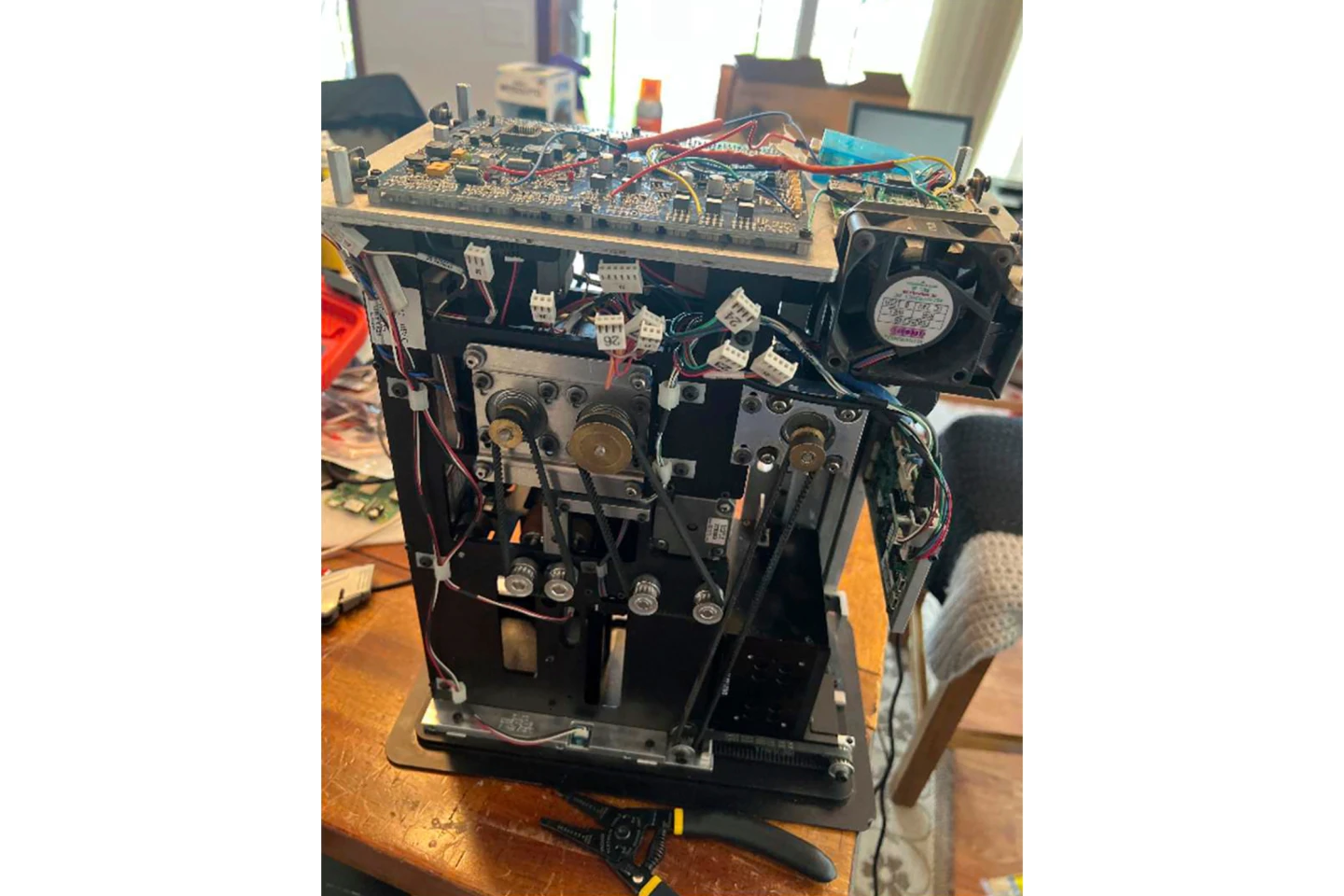

Despite the bleak outlook, some experts believe there may still be hope for the watch-making industry. Dr. Umar Abdulmajid suggests that the rise of smartwatches could rejuvenate interest in traditional watch services, urging artisans to adapt and expand their skills. However, Baba Bala, who returned to Kaduna two decades ago to be closer to family, shows little interest in diversifying into new technologies. "This is what I love doing," he asserts, calling himself a "doctor for sick wristwatches."

As he sits alone in his shop, often accompanied by only a radio playing Hausa programs, Baba Bala remains resilient. His family continues to support him, with his eldest daughter assisting with bills during tough times. His youngest son has expressed interest in flying, aiming for a career as a pilot, but Baba Bala is hesitant to encourage him to pursue watch repairing.

While he clings to the memories of a bustling business, the reality of an evolving world looms large, challenging the enduring legacy of a skilled craftsman in the wake of technological change.