Thanh, a self-proclaimed Vietnamese people smuggler currently seeking asylum in the UK, has shed light on the murky world of human trafficking that has led many of his compatriots to risk their lives crossing the English Channel. In a chilling interview, he details how he has been entrenched in the smuggling industry for nearly 20 years, claiming to have assisted over 1,000 individuals in their perilous journey to the UK.

Entering the UK illegally in 2023 via small boats, Thanh is aware of the risks involved but insists that the profit margins are significant. He has honed his craft in forging visa documents for those planning similar crossings, claiming this has become a lucrative, albeit dangerous, business. Vietnamese migrants are now noted as the largest group attempting to enter the UK, often motivated by economic hardships and debts from back home.

In the shadow of the ongoing migrant crisis, Thanh discloses how many Vietnamese individuals pay upwards of $15,000 to make the journey from Vietnam to the UK. This hefty price tag underscores the desperation of these individuals, many of whom resort to unauthorized pathways to secure better opportunities.

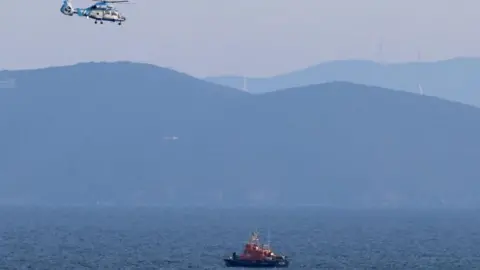

Despite the perils associated with this trade — more than 50 fatalities in the Channel this year alone — Thanh explains how smugglers often use innovative methods to evade authorities, including the forging of legitimate visa paperwork for clients. However, he contends this is not a trafficking operation but a service to individuals seeking a way out of dire circumstances.

During the course of the conversation, Thanh also admits to fabricating stories of his own victimization to secure asylum. He asserts that many migrants falsely claim they have been trafficked as a strategy to navigate the asylum process. This presentation of the smuggling landscape showcases a fragmented yet complex network whereby individual actors, like Thanh, quite consciously operate within a grey legal area.

Experts and NGOs, on the other hand, offer contrasting views on the trafficking issue, with some arguing that a significant number of Vietnamese migrants indeed fall victim to exploitation. They emphasize the need for safe migration routes to prevent individuals like Thanh from profiting off desperation.

Reflecting on his past, Thanh expresses a mix of regret and resignation, portraying himself as trapped within the cycle of crime that he enabled. Despite his attempts to justify his actions, he ultimately acknowledges the pervasive dangers and limitations of illegal migration, recommending that those in Vietnam reconsider the risks before engaging in such treacherous endeavors.

His story highlights the broader implications of the ongoing migration crisis and serves as a grim reminder of the lengths individuals will go to in pursuit of a better life amidst widespread hardship and the allure of myths surrounding overseas opportunities.