Lizbeth Perez looks fearful as she gazes out onto the postcard-perfect fishing bay of Taganga, on Colombia's Caribbean coast, recalling the moment she last spoke to her uncle in September.

He was a kind man, a good person, a friend. A good father, uncle son. He was a cheerful person. He loved his work and his fishing, she said.

Alejandro Carranza said goodbye to his family early on the morning of 14 September, before going out on his boat as usual, his cousin Audenis Manjarres told state media. He left from La Guajira, a region in neighbouring Venezuela, he said.

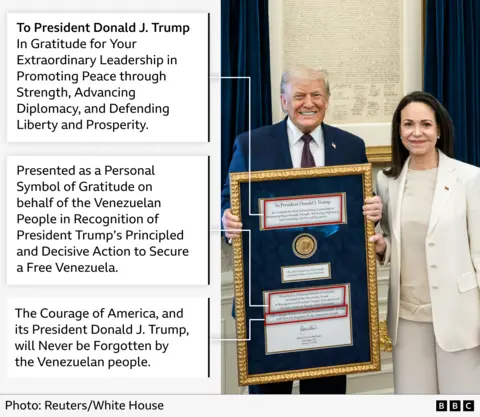

The following day, US President Donald Trump announced that a US strike in international waters had targeted a vessel that had departed Venezuela, killing three individuals described as extraordinarily violent drug-trafficking cartels and narco-terrorists. Since then, Ms. Perez has not seen her uncle, leaving his five children longing for their father.

The truth is we don't know it was him, we don't have any proof that it was him, apart from what we saw on the news, she stated, reflecting her family's emotional turmoil.

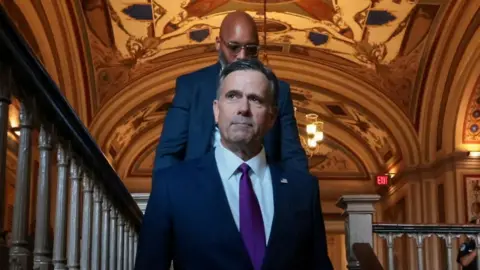

The US strikes, which began in September, have resulted in at least 21 operations with claims of 83 fatalities. US officials, like Defence Secretary Pete Hegseth, assert the actions aim to eliminate narco-terrorists from our hemisphere and safeguard the US from drugs entering the country.

However, these operations have drawn sharp criticism from regional officials, raising legal and moral questions regarding their implementation. Colombian President Gustavo Petro expressed concern about the loss of Colombian citizens, stating that Carranza was among those killed in the strike.

In response, the US administration has demanded a retraction of Petro's allegations, fostering tensions between the two countries. Trump has also confronted Petro, accusing him of fostering drug production.

Critics argue that the strikes often violate international law, with some calling them extrajudicial killings that unjustly endanger civilian lives. Family members of victims like Carranza, supported by legal advocates, are considering suing the US government, insisting that even if wrongdoing is suspected, due process must be followed.

Locals in Taganga and fishermen, including 81-year-old Juan Assis Tejeda, now live in fear, concerned they could be mistakenly targeted amid the aggressive enforcement against drug trafficking. They have witnessed the presence of drones and military, leading them to question the extent and motivations of US intervention in the region.

As the US navigates policies regarding drug-related violence and its implications, the fishing communities in Colombia face an uncertain future, wondering whether further military actions will arise or if diplomatic solutions are possible.