When Keira's daughter was born last November, she was given two hours with her before the baby was taken into care.

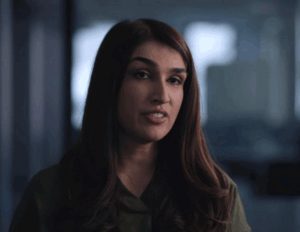

Right when she came out, I started counting the minutes, Keira, 39, recalls.

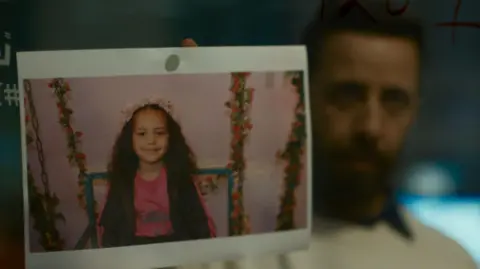

I kept looking at the clock to see how long we had. When the moment came for Zammi to be taken from her arms, Keira says she sobbed uncontrollably, whispering sorry to her baby. It felt like a part of my soul died. Now Keira is one of many Greenlandic families living on the Danish mainland who are fighting to get their children returned to them after they were removed by social services.

In such cases, babies and children were taken away after parental competency tests - known in Denmark as FKUs - were used to assess whether they were fit to be parents. In May this year, the Danish government banned the use of these tests on Greenlandic families after decades of criticism, although they continue to be used on other families in Denmark.

The assessments are utilized in complex welfare cases where authorities suspect children are at risk of neglect or harm. They involve interviews with parents and children, cognitive tasks, and emotional assessments. Defenders argue they provide objective evaluations, while critics claim they cannot accurately predict parenting capability and are steeped in cultural bias against Greenlanders.

Greenlanders, as Danish citizens, have been found to be significantly more likely to have their children taken into care compared to Danish parents. After the recent government ban, hopes have been raised for families like Keira’s, yet the actual review and return of children have seen little progress.

Keira asserts that despite these challenges, she remains determined to reunite with her daughter Zammi, keeping a cot ready for her return and continuing cultural connections through her visits.

Many parents share heartbreaking stories of loss and struggle, with some still fighting for recognition and justice as authorities grapple with the implications of their past policies.