For India, few friendships have been as strategically valuable - and as politically costly - as its long embrace of Bangladesh's former leader Sheikh Hasina.

During 15 years in power she delivered what Delhi prizes most in its periphery: stability, connectivity and a neighbour willing to align its interests with India's rather than China's.

These days she is across the border in India but has been sentenced to death by a special tribunal in Bangladesh for crimes against humanity over her crackdown on student-led protests, which led to her ousting.

The 2024 demonstrations forced her to flee and paved the way for Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus to lead an interim government. Elections are due early next year.

The fallout from all this has created a diplomatic bind: Dhaka wants Hasina extradited, but Delhi has shown no inclination to comply - making her death sentence effectively unenforceable.

What Delhi intended as humanitarian asylum is turning into a long and uncomfortable test of how far it is willing to go for an old ally, and how much diplomatic capital it is prepared to burn in the process.

Michael Kugelman, a South Asia expert, says India faces four unappealing options.

It could hand Hasina over - which it really doesn't want to do. It could maintain the status quo, though that will become increasingly risky for Delhi once a newly elected government takes office next year.

Or, it could press Hasina to stay silent and avoid statements or interviews, something she is unlikely to accept as she continues to lead her Awami League party - and something Delhi is unlikely to enforce.

The remaining option is to find a third country to take her in, but that too is fraught: few governments are likely to accept a high-maintenance guest with serious legal problems and security needs, Mr Kugelman says.

Extraditing Hasina is unthinkable - India's ruling party and opposition alike view her as a close friend. India prides itself on not turning on its friends, according to Mr Kugelman.

What makes this moment especially awkward for Delhi is the sheer depth - and asymmetry - of the India–Bangladesh relationship, rooted in India's pivotal role in Bangladesh's birth.

Bangladesh is India's biggest trading partner in South Asia, and India has become Bangladesh's largest export market in Asia. Total trade reached nearly $13bn (£10bn) last year, with Bangladesh running a sizeable deficit, heavily dependent on Indian raw materials, energy and transit routes.

India has offered $8bn-$10bn in concessional credit over the past decade, provides duty-free access to some goods, built cross-border rail links, and supplies electricity - plus oil and LNG - from Indian grids and ports. This is not a relationship either side can easily walk away from.

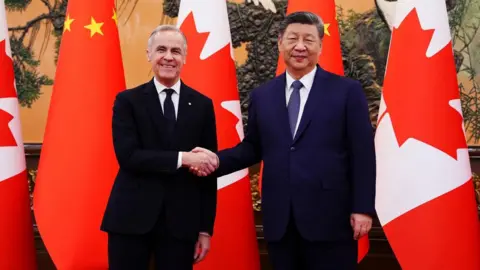

Yet, many believe, Bangladesh's interim government, under Yunus, appears to now be moving quickly to rebalance its external ties. His first months in office have been a burst of diplomatic outreach aimed at de-Indianising Bangladesh's foreign policy.

A government that once aligned itself with India at every regional forum is now cancelling judicial exchanges, renegotiating Indian energy deals, slowing India-led connectivity projects, and leaning publicly on Beijing, Islamabad and even Ankara for strategic partnership. Many believe the message could not be clearer: Bangladesh, once India's most dependable neighbour, is hedging hard.

Prof Bharadwaj says that long-standing economic and cultural ties often endure beyond political shifts: data show that trade between India and Bangladesh grew between 2001 and 2006, when the less friendlier Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), in coalition with Jamaat-e-Islami (JeI), was in power. While diplomatic and political relations often fluctuate with changes in government, economic, cultural and sports ties tend to remain largely stable. Even if a new administration is less friendly toward India, it does not automatically disrupt trade or broader bilateral relations...

For Delhi, the challenge is not just managing a fallen ally in exile, but preserving a neighbour central to its security - from counterterrorism and border management to access to its restive north-eastern region. India shares a 4,096km (2,545 mile) largely porous and partly riverine border with Bangladesh, where domestic turbulence could trigger displacement or mobilisation of extremists, experts say.

Dr Paliwal believes the relationship is likely to remain turbulent over the next 12–18 months, with the intensity depending on developments in Bangladesh after next year's elections. If the interim government is able to pull off elections with credibility, and an elected government takes charges, it could open options for the two sides to renegotiate the relationship and limit the damage.

Ultimately, the next elected government will need to balance Bangladesh's core interests - border security, trade and connectivity - against domestic politics and public anti-India sentiment. I don't anticipate a serious crisis in ties, but I suspect they'll remain fragile at best.