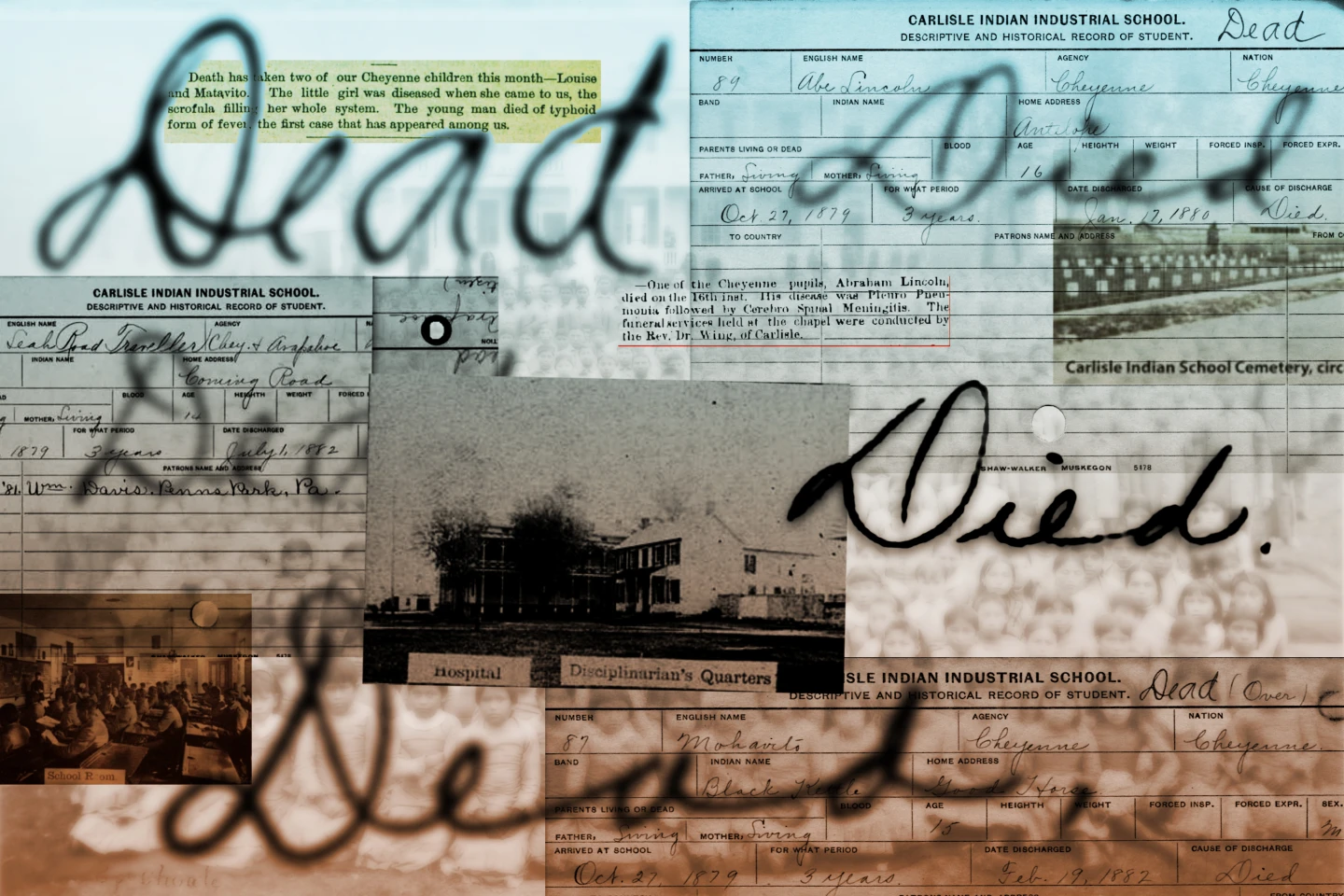

The Carlisle Indian Industrial School was a notorious institution for Native American children, established to forcibly assimilate young Indigenous people into Euro-American culture. Matavito Horse and Leah Road Traveler were among the first to be taken there in 1879, part of a systematic approach by the U.S. government to erase Native identities through education. Tragically, both children died a few years later, victims of the harsh conditions of the boarding school's environment.

Recent initiatives have seen the repatriation of 17 children's remains to their tribes after persistent advocacy by Native communities. The Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes have received 16 of these students, laying them to rest in a cemetery in Oklahoma, while another, Wallace Perryman, has been returned to the Seminole Nation.

The burial ceremonies have been described as essential steps towards justice for families impacted by the boarding school era. Sadly, many details about these children's lives, including their families and the circumstances of their deaths, remain lost or misrepresented in historical records.

Matavito Horse was recorded as the first typhoid victim at Carlisle; however, the reasons for Leah's death are unclear. The school’s legacy involves numerous instances of abuse and neglect, which have been substantiated by multiple reports detailing physical, sexual, and emotional trauma inflicted upon students over decades.

Despite a complex legacy, numerous tribes are actively working towards the identification and repatriation of their children’s remains, facing challenges due to inadequate documentation and systemic barriers involving federal policies. In contrast, the benefits of repatriation are significant: they not only restore dignity but also provide families and communities with closure, as well as an opportunity for healing. This critical journey underscores the relentless efforts of tribal leaders and community members to ensure the recognition and restoration of their histories.

Recent initiatives have seen the repatriation of 17 children's remains to their tribes after persistent advocacy by Native communities. The Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes have received 16 of these students, laying them to rest in a cemetery in Oklahoma, while another, Wallace Perryman, has been returned to the Seminole Nation.

The burial ceremonies have been described as essential steps towards justice for families impacted by the boarding school era. Sadly, many details about these children's lives, including their families and the circumstances of their deaths, remain lost or misrepresented in historical records.

Matavito Horse was recorded as the first typhoid victim at Carlisle; however, the reasons for Leah's death are unclear. The school’s legacy involves numerous instances of abuse and neglect, which have been substantiated by multiple reports detailing physical, sexual, and emotional trauma inflicted upon students over decades.

Despite a complex legacy, numerous tribes are actively working towards the identification and repatriation of their children’s remains, facing challenges due to inadequate documentation and systemic barriers involving federal policies. In contrast, the benefits of repatriation are significant: they not only restore dignity but also provide families and communities with closure, as well as an opportunity for healing. This critical journey underscores the relentless efforts of tribal leaders and community members to ensure the recognition and restoration of their histories.