At a bus stand in the northern Indian city of Lucknow, the anxious faces tell their own story.

Nepalis who once came to India in search of work are now hurrying back across the border, as the nation reels with its worst unrest in decades. We are returning home to our motherland, says one man. We are confused. People are asking us to come back.

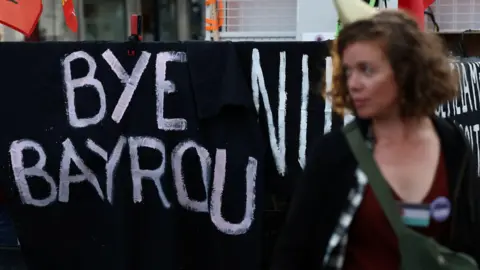

Earlier this week, Nepal's Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli quit after 30 died in clashes triggered by a social media ban. While the ban was later reversed, Gen Z-led protests raged on. A nationwide curfew is in place, soldiers patrol the streets, and parliament and politicians' homes have been set ablaze. With Oli gone, Nepal has no government in place.

For migrants like Saroj Nevarbani, the choice is stark. There's trouble back home, so I must return. My parents are there - the situation is grave, he told BBC Hindi. Others, like Pesal and Lakshman Bhatt, echo the uncertainty. We know nothing, they say, but people at home have asked us to come back.

For many, the journey back is not just about wages or work - it is bound up with family ties, insecurity, and the rhythms of migration that have long shaped Nepali lives. Nepalis in India, after all, fall broadly into three groups.

First, there are the migrant workers who leave families behind to work as cooks, domestic help, security guards, or in low-paid jobs across Indian cities. They remain Nepali citizens, move back and forth, lack Aadhaar (India's biometric identity card) and are often denied basic services. That is why sometimes they are called seasonal migrants.

Second, those who relocate with their families, build lives in India, and often obtain the identity card, yet retain Nepali citizenship and ties to home, even returning to vote.

Third, there are Indian citizens of Nepali ethnicity - descendants of earlier waves of migration in the 18th to 20th Centuries - who are rooted in India but still claim cultural kinship with Nepal.

Nepal also tops the list of foreign students in India, with more than 13,000 out of some 47,000, according to the latest official data. There are many other Nepalese who cross the 1,750km (466 miles) open border for medicine, supplies, or family visits, eased by a 1950 peace and friendship treaty and strong social networks.

New Nepali migrants entering India's labour market are typically 15–20 years old, though the overall median age is 35, according to Keshav Bashyal of Kathmandu's Tribbuvan University. Joblessness and rising inequality drive migration, especially among the poor, rural and less educated, whose labour force participation is already low.

Most come from poorer backgrounds, working in construction and religious sites in Uttarakhand, on farms in Punjab, in factories in Gujarat, and in hotels across Delhi and beyond.

This steady flow of young migrants feeds into a sizable, though largely invisible, workforce in India. Due to the open border, it is difficult to know the exact number of Nepali citizens working and living in India but is estimated to be around 1-1.5 million.

Nepal's reliance on its migrants is staggering. In 2016-17, remittances made up over a quarter of Nepal's GDP, and by 2024 they accounted for 27–30%. Over 70% of households receive them.

Yet, for all their economic importance, Nepali migrants in India often live precariously. A study in Maharashtra found them squeezed into squalid shared rooms, with little sanitation, often facing discrimination at work and in clinics. Alcohol and tobacco use was high, and sexual health awareness was low. Social networks were found to be both lifeline and liability.

Another study in Delhi found Nepali migrants were working for basic survival rather than improvement in their living standards.

Take the case of Dhanraj Kathayat, a security guard in Mumbai. He arrived in India in 1988, a young man seeking work, and has since been winded through cities - Nagpur, Belgaum, Goa, Nasik - before settling in the western metropolis. He began driving but has spent the past 16 years guarding buildings, a job that offers some security but little upward mobility.

I haven't thought much about what's happening back home, he told me. There's so much joblessness in Nepal, even those with education find it difficult to find work. That's why people like me had to leave.

This type of political crisis deepens the problems of youth unemployment in Nepal. Analysts suggest that long-term instability could lead to increased migration to India, where many already navigate informal labor markets with limited security.

Ultimately, for most Nepalis, the border is more of a lifeline than boundary - offering survival and opportunity in India while keeping them tied to the politics of their home.