The day they appeared he could hardly believe his eyes. Small boat after small boat bearing in from the Turkish side. I have so many memories that are coming back to me now, says Paris Laoumis, 50, a hotelier on the Greek island of Lesbos. There were people from Syria, Afghanistan, many countries. This was August 2015 and Europe was witnessing the greatest movement in population since the end of the Second World War. More than a million people would arrive in the EU over the next few months driven by violence in Syria as well as Afghanistan and Iraq.

I witnessed the arrivals on Lesbos and met Paris Laoumis as he was busy helping exhausted asylum seekers near his hotel. I am proud of what we did back then, he tells me. Along with international volunteers, he provided food and clothing to those arriving.

Today, the beach is quiet. There are no asylum seekers. But Paris is worried. He believes another crisis is possible. With the number of arrivals rising over the summer months, his country's migration minister has warned of the risk of an invasion, with thousands arriving from countries such as Sudan, Egypt, Bangladesh, and Yemen.

In 2015, asylum seekers boarded ferries and trudged in the heat along railway lines, through cornfields, down country lanes, and along highways, making their way up through the Balkans to Germany and Scandinavia. The numbers entering Germany jumped from 76,000 in July to 170,000 the following month. On the last day of August, Chancellor Angela Merkel declared 'wir schaffen das' - we can do it - interpreted by many as extending open arms to the asylum seekers.

Merkel asserted, Germany is a strong country. The motive with which we approach these things must be: we have achieved so much—we can do it! But the high emotions of that summer, when crowds welcomed asylum seekers along the roads north, seem to belong to a very different time.

That optimistic proclamation soon became a political liability for Mrs. Merkel. Political opponents and some European leaders felt the words acted as a magnet for asylum seekers to the EU. Within a fortnight, the Chancellor was forced to impose controls on Germany's borders due to the influx of asylum seekers.

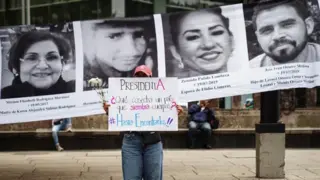

A decade on, concerns over migration have become a major political issue in many European countries, with security concerns, struggling economies, and disillusionment with governing parties shaping attitudes towards those fleeing war, hunger, and economic desperation.

In Hungary, Prime Minister Viktor Orban's far-right government has taken one of the toughest approaches to migration. In September 2015, Hungary began erecting fences along its border with Serbia and has since returned many who arrive without permission.

Hungary's policies have drawn criticism, with human rights lawyers arguing they effectively eliminate legal migration routes into the EU for refugees. Despite EU fines for Hungary for breaching asylum obligations, the government maintains that protecting its borders and preserving stability is worth the cost.

The climate of the response to immigration has shifted throughout Europe; support for far-right parties has surged, particularly in countries like Sweden. Once a nation known for its hospitality towards refugees, Sweden has seen a rise in anti-immigration sentiments, with policies hardening under pressure from populist parties.

The consequences of political decisions in Europe are clear: significantly fewer asylum seekers now reach its shores, yet global conflicts persist, ensuring that migration trends are likely to continue. While strict policies may limit numbers temporarily, they do not address the underlying factors driving people to seek safety and better lives in Europe.

This multifaceted crisis poses ongoing challenges for European leaders, compelling them to find humane solutions amid rising political tensions and public anxiety.