Two million books, housed across a sprawling building, free for anyone to borrow and read.

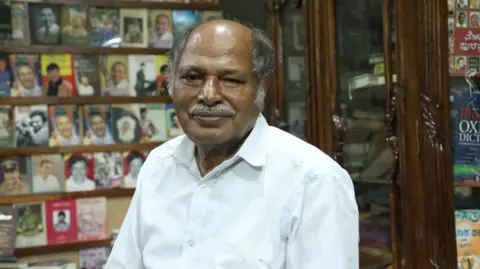

That's the wealth that Alphonse Vimulraj Anke Gowda, a retired sugar factory worker from India's southern Karnataka state, has accumulated over the past five decades.

The 79-year-old made headlines last month when he received the Padma Shri - a civilian honour awarded by the federal government - for his extraordinary contribution to promoting literacy and learning.

Gowda - whose eye-popping collection includes rare editions of the Bible, along with books on every subject imaginable - comes from a farming family where books were a luxury.

I grew up in a village. We never got books to read, but I was always curious about them. I kept thinking that I should read, gather books and gain knowledge, he told the BBC.

Gowda's library is located in Pandavapura, a small municipality in Karnataka's Mandya district. It lacks the rigid organisation usually associated with libraries. In fact, Gowda's collection doesn't have a librarian and books are stacked on shelves and piled on the floor in a haphazard manner.

Outside, under the library's awnings are sacks filled with an estimated 800,000 books, still waiting to be unpacked. The collection is still growing, through Gowda's purchases and donations from others.

The place is frequented by students, their parents, teachers and book lovers. Regular visitors seem to know their way around the library and find the books they need with ease. And even if they can't, they say, Gowda can find anything.

Gowda, his wife and son live in a corner of the library, which is open every day of the week - and for long hours.

Gowda spent his childhood juggling school and helping his father with farm work. He would often ask his parents and elder sister for money to buy books. When he began reading books about Indian freedom fighters and spiritual leaders, he got hooked.

Inspired by a teacher, he started building a small collection of books so that other students from rural areas could also read. He often used the money his parents gave him for food to buy books instead.

His next hurdle would be familiar to book lovers everywhere - finding space to house his overflowing collection.

I started keeping the books in trunks [large metal boxes]. Then I installed bookshelves in my house. But at one point, there was no place left, he says.

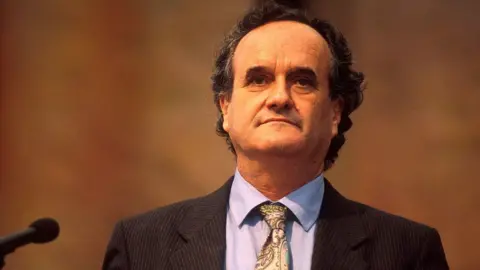

Help came when some of his friends met Hari Khoday, the late liquor baron who was building a temple in Pandavapura. Khoday, recalls Gowda, couldn't believe that one man could own so many books.

Today, students and teachers from across the state visit the library. Among them is Ravi Bettaswami, an assistant professor at a private college who says that he has also been inspired to build a collection of thousands of books.

When asked why he never hired a librarian, Gowda says no-one ever suggested that to him. As for the future of the library, Gowda strikes a philosophical note, suggesting that it is now up to others to take his legacy forward.