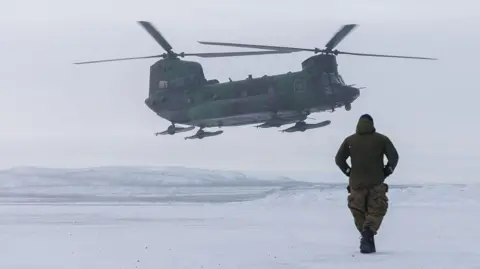

Canada's Arctic is a massive, treacherous, and largely inhospitable place, stretched out over nearly 4 million square kilometres of territory - but with a small population roughly equal to Blackburn in England or Syracuse, New York.

You can take a map of continental Europe, put it on the Canadian Arctic, and there's room to spare, Pierre Leblanc, the former commander of the Canadian Forces Northern Area told the BBC. And that environment is extremely dangerous.

Standing at the defence of that massive landmass is an aging string of early warning radars, eight staffed military bases and about 100 full-time Coast Guard personnel covering 162,000km of coast, about 60% of Canada's total oceanfront.

The Arctic region is the scene of intense geopolitical competition, bordered by Russia and the US on either side of the North Pole - and increasingly attractive to China, which has declared itself a near Arctic state and vastly expanded its fleet of naval vessels and icebreakers.

Standing in the middle is Canada, whose population is a small fraction of the larger Arctic players.

Nearly four years after Arctic security was thrust into the headlines following Russia's invasion of Ukraine, the defence of Canada's far north has again been brought to the forefront of public consciousness by Donald Trump's designs on Greenland, a self-governing part of the Kingdom of Denmark that the White House says is vital to safeguarding the US from would-be enemies abroad.

Canada's Arctic has not gone unnoticed by the Trump administration, which has reportedly become increasingly concerned by perceived vulnerabilities to US adversaries, and in April signed an executive order underscoring American commitment to ensuring both freedom of navigation and American domination in the Arctic waterways.

The Canadian government, for its part, has sought to reassure the US and NATO allies that it is doing its part to protect the region.

Speaking at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Prime Minister Mark Carney said that Canada is working to secure our shared objectives of security and prosperity in the Arctic through unprecedented investments in radar systems, submarines, aircraft and boots on the ground in the region.

Col Leblanc, who spent a total of nine years in the Canadian Arctic, said those investments have marked a major shift in Arctic security, noting that increases in Canadian defence expenditure from 2% to 5% of GDP by 2035 have meant real action in terms of additional over-the-horizon radar and aircraft dedicated to the Arctic.

Much of this focus, he added, has been prompted by the Trump administration's renewed focus on the Arctic and Greenland.

Still, challenges persist, including limited port facilities and difficulties resupplying far-flung bases that are sometimes thousands of cold, empty miles apart.

While Canada and other US NATO allies have opposed the Trump's administration bid to take over Greenland to protect the Arctic, several experts who spoke to the BBC agreed with the administration's broad assessment that the need for additional defences in the region are urgently needed.

Troy Bouffard, the director of the Fairbanks, Alaska-based Center for Arctic Security and Resilience, said while on-the-ground cooperation between the US and Canada in the Arctic remains the envy of the world, much of the existing defence infrastructure was designed to combat Cold War-era threats, rather than existing ones.

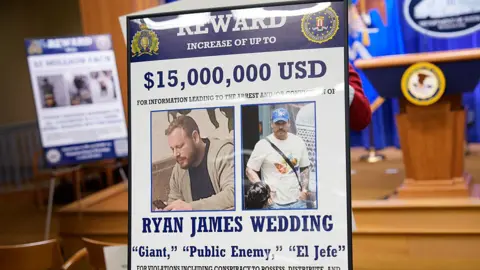

In particularly alarming terms, he warned of the prospect of hypersonic missiles that travel at least five times the speed of sound, making them much harder to detect and intercept than traditional ballistic missiles, which would follow predictable arcs over the North Pole.

Such a threat is no longer theoretical; Russia has used hypersonic missiles in combat in Ukraine, including a January strike that saw the first operational use of the nuclear-capable Oreshnik missile that carries multiple warheads at approximately 10 times the speed of sound.

That technology has changed everything for us. We have to relook at the entire North American defence system and re-do it, he said. What exists right now cannot defend against hypersonic cruise missiles, at all. Like 0%.

Traditional ground-based radar systems, he added, are not going to work against these emerging technologies. Space-based satellites must also contend with coverage gaps in high latitudes, prompting a renewed focus and investments in over-the-horizon radar.

In recent discussions, it has also been noted that over-the-horizon technology, along with space-based sensors, form a key part of the Trump administration's planned Golden Dome missile defence system for North America.

For now, it is unclear what role Canada will play in the Golden Dome, a project Trump said at Davos Canada should be thankful for. Trump's remarks prompted Canada's ambassador to the UN, Bob Rae, to compare it to a protection racket. There are concerns that negotiations have been strained by the often adversarial relationship between the US and Canada.

Despite tensions, some experts argue that American concerns over Arctic security, paired with their threats of tariffs, have prompted the Canadian government to re-focus on the Arctic. Michael Byers, an expert in Arctic security at the University of British Columbia, said, Whether or not American concerns are justified, there is a feeling in Ottawa that we have to satisfy [them]. High-level tensions between Ottawa and Washington have yet to turn into on-the-ground tensions in the Arctic, with practitioners in the area expressing confidence that the US and Canada are cooperating for the time being.